Talking to Children about Race: The Elementary School Years

This blog is the second in a series designed for caregivers to more easily approach the topic of race, bias, and racism with their children. Much of the language and resources in the Birth to Pre-K blog is also appropriate for Kinder and 1st graders and is generally foundational to this post. Please check it out!

As we began to lay out in the previous blog, beliefs and values around race and racism begin to emerge and solidify during these early years. The greatest levels of prejudice are shown when children are four to seven years old, and the prejudices gradually decline after age seven (1). It is crucial to have these conversations around race before your child has reached seven years, to ensure that those prejudices don’t continue as they grow older. Of course, if you have older kids, it’s never too late to begin these conversations, either! Continue to check out the blog in the coming months as we continue to discuss how to have these conversations with your middle school and high school students.

Many of us are gearing up for back to school, and this is a great time to begin thinking or continue thinking, of how the conversations with race can continue when your child is in school. Creating a foundation and an environment where anti-racism is actively practiced at home is important, but you need to continue to help your children develop their knowledge and understanding for when they are out of your house and away from your family.

Your Child’s Environment—School

Now that your children are in elementary school, they are going to be exposed to more people and ideas than your home and your family. Your child’s teachers, classmates, and other individuals at the school may not actively practice anti-racism and might say things that are contrary to how you are hoping to raise your child. Let your children know that they might hear things at school that your family doesn’t believe in. Remind them that they can always talk with you and share with you when they hear those things. Validating their feelings, observations, and experiences and taking interest in their thoughts, feelings, and ideas shows them that you are a person they can talk with about anything, even race.

At the beginning of the school year, take the opportunity to talk with your child’s teacher. Inquire about the toys, books, and movies that will be watched during class time. Are there diverse representations? Will these materials be a balance of mirrors and windows for your child and the other children in the classroom? Are there people with different body types, nationalities, gender identity, and religions being discussed? Are there opportunities during class for the students to learn from one another? What holidays are being celebrated in the classroom, or at the school? How are concepts such as equity and inclusion being presented in the class over the course of the academic school year? Will discussions and conversations about race and racism be part of the curriculum? Research has shown that children across grade levels are able to discuss racism and its nuances when their teachers gradually build them toward this (2).

Use this time to get your teacher’s input as well! What resources, books, movies, or toys do they recommend to help continue the conversation about anti-racism with your child? What are the ways that you can expand on what they are learning in the classroom at home? How can you be a team with your child’s teacher as you both engage in the education of your child? You are not alone in this journey, and you should work with those who are on your team to help you with every step of the way.

This might also be a time to think about what you can do on your own to supplement the education your child is receiving in school. Textbooks, specifically history and government textbooks, have sometimes glossed over, or completely removed, large parts of American and world history. Talking with your child at home, watching movies, or reading books will help to give them a more well-rounded history of our country, as well as provide context and understanding about the topics they are studying in school.

A great way to encourage critical thinking and perspective-taking is to ask your child:

Who is represented?

Who is missing?

Who benefits from the story or lesson, especially as it relates to history?

When we begin to think of who is represented in our textbooks, largely white Protestant men who “conquered” the “new world”, it allows for greater conversations around who is missing, the perspective of the Indigenous people, the enslaved, alleged witches, other ordinary women, white indentured servants, and BIPOC. It also lets children think about why certain stories might be ignored, and who benefits when we ignore those stories. At this age, children can clearly distinguish between right and wrong, fair and unfair. These questions can help your child to begin to understand the intricacies of history in a way that makes sense for their level of development.

If you are able to, get involved in your child’s school beyond the classroom level. Joining the Parent Teacher Association is a way to ensure equity and inclusion is being practiced throughout the school, not just in the classroom that your child is currently enrolled in. Your child won’t stay in one grade, and one classroom forever! Attending school board meetings can also be a way to know what is happening at a district level, and allow you to have more of an opinion on what is happening at your child’s school. These meetings might be hard to attend, but often they are available online or notes from the meetings are posted to the school board website. Addressing equity and inclusion also requires that we confront our own biases and ideals of what is important in education. If you haven’t already, consider some of the recommendations here to encourage your own growth.

Your Child’s Environment—Home

Continue to show your child that you are a safe place for them to ask questions, that it is okay to ask questions, and that you want to help them learn. Remember, you don’t have to know everything! Anti-racism is a lifelong journey and something that we are all continuing to learn about. Showing your child that you are still learning can be helpful to them, encouraging their own continued education and showing the importance of lifelong learning.

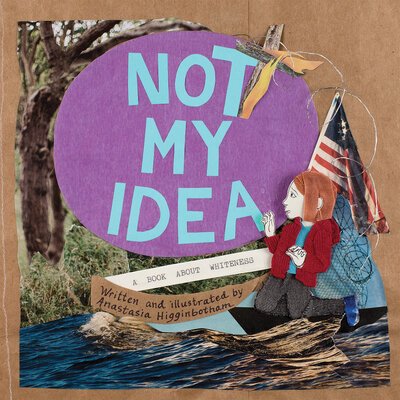

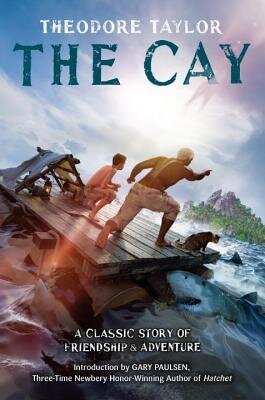

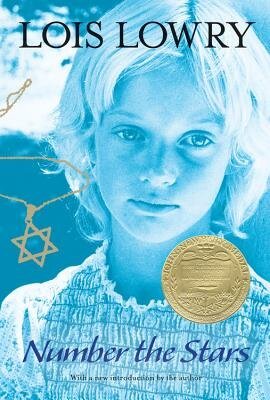

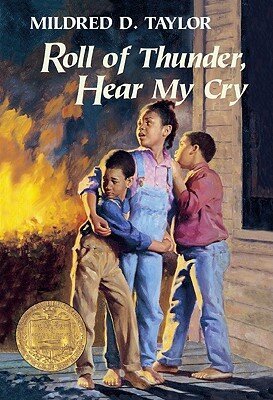

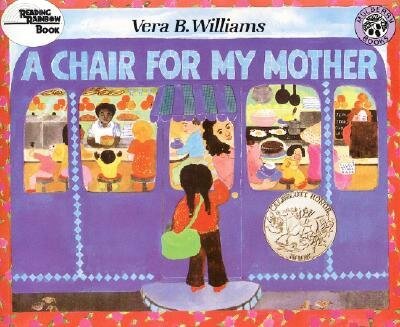

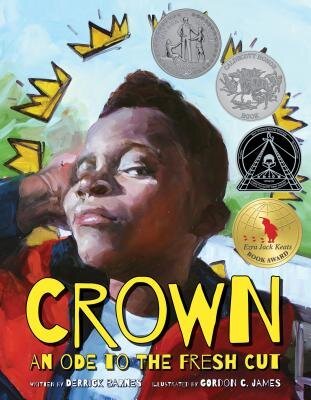

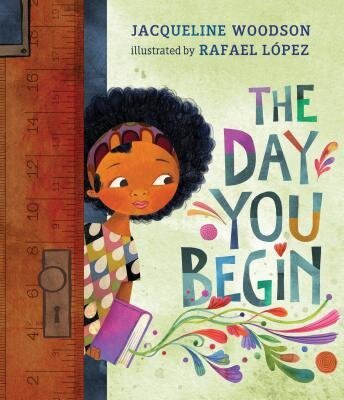

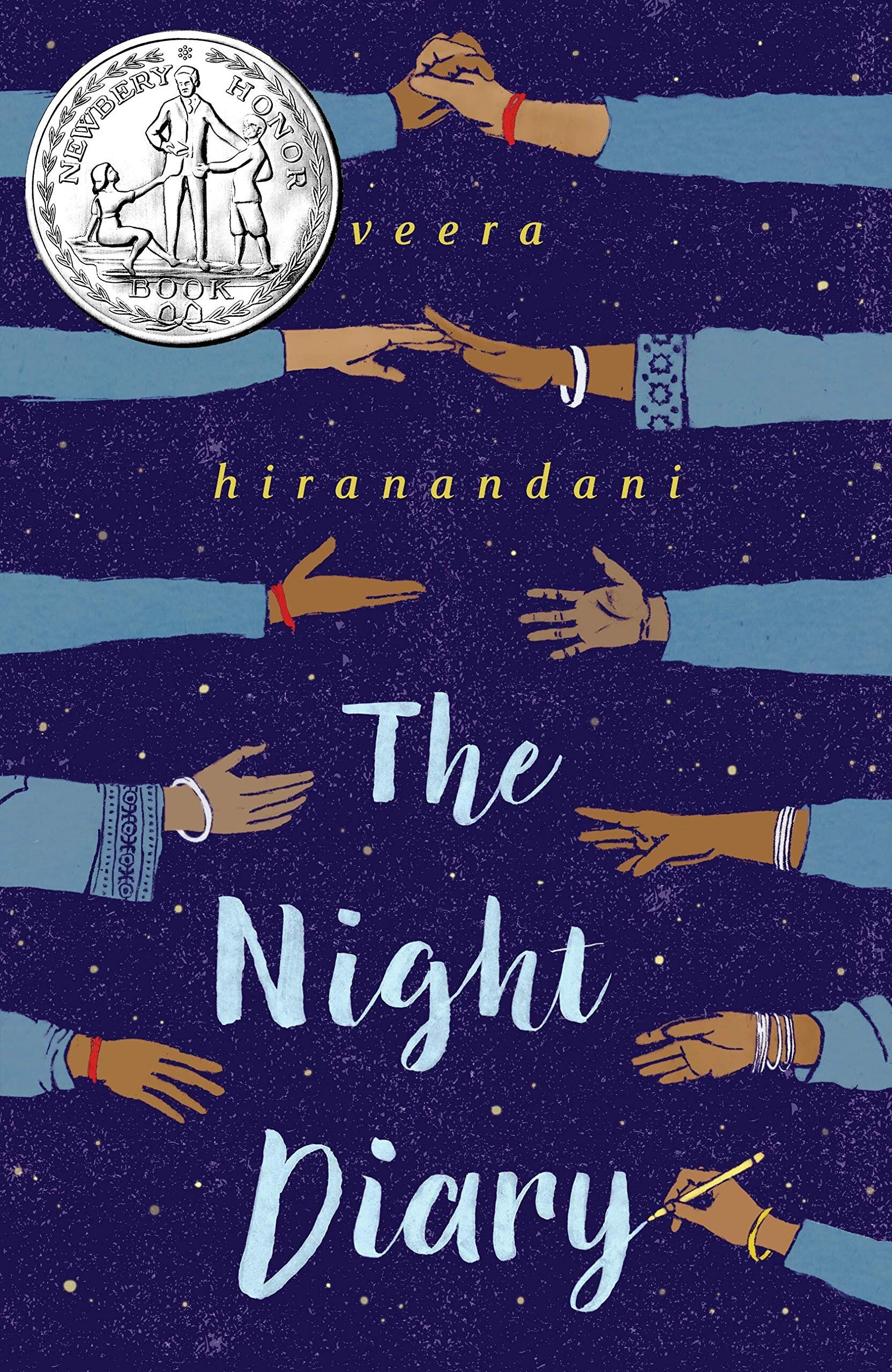

Continue to model and celebrate diversity throughout your house. Do this through books, toys, movies, television shows that you have for your child, as well as anything that you watch or play as a family. There are several children’s books that discuss topics around race, ethnicity, racism, and civil rights that are appropriate for these grade levels and these levels of understanding. You can find some of our favorite books for children in this age group below:

Your Child’s Environment—The World Around Them

As you continue to talk to your child about what they are learning in school, and what you are reading and talking about at home, encourage them to think about the diversity in the world around them. Though the world may seem large to your child, it is a small piece of the entire world and all the people in it.

Search for clubs and activities offered at your school that allow your child to explore different cultures or groups outside of your own. Look for those groups and activities outside of school as well. Attend holidays and events in your town or in towns around you that celebrate different cultures, and allow your child to experience the beauty that comes from others’ perspectives and celebrations.

Remember, while it is important to introduce your child to different cultures and different ethnic groups, you don’t want appropriate cultures from other people. Cultural appropriation has many different definitions, but one way is to think about it as, “the adoption of certain elements from another culture without the consent of people who belong to that culture.” Cultural appropriation can be seen throughout American society in music, fashion, makeup, and even the way we talk. When you are learning about different cultures and different cultural values, use respect and sensitivity.

Your Child—Learning Through Questions

Your child might not be out of the questioning phase, but they have left behind some of the “But, why?” questions that toddlers are well known for! Instead, the questions you’re being asked might be more detailed or might want to know more information about some of the concepts you have been talking with them about before.

We provided some language in our previous blog for all those “why” questions caregivers are oh so familiar with especially as it relates to observable differences like skin color or tone. Many white caregivers of the generation caregiving small children now were raised not to “see color” or with the messaging that talking about race was improper or rude. Now, we know better. So, now we can do better.

Sweeping the topic under the rug does not undo historical oppression and inequity. When our elementary-age kids begin asking questions that have their roots in systemic racism, age-appropriate responses are key. Late elementary school is when we can graduate from framing racism as unfairness and provide more context. But, we’ve got to have the context and history ourselves!

We need to take the opportunities when our children ask questions to educate, even though it is so easy to say, “I don’t know,” whenever our kids ask questions that require extra brainpower on our end. Your answers do not have to be perfect, and as we have said before, you do not need to know everything. Give them context, give them a basic understanding, explain what you know, and allow for opportunities to learn together.

For example, when our kids’ eyes are open to the realization that their school is more white than another school in the district, you could begin a conversation around equity saying, “Our country was created based on racism, you know, like believing Black people were less than us, and it was okay to enslave them. Now we know that is not true and that’s why slavery doesn’t exist anymore. But sometimes, there are people with that incorrect thinking still today. White people have had a lot more opportunities than non-white people because of that belief, so many white families now have more opportunities to live in certain neighborhoods with better access to resources and opportunities.” This provides the context of history, a discussion of equity, and opportunities to discuss how not all people practice anti-racism as your family does.

If your child wonders why that police officer was so stern or mean to that Black man, you could say “That police officer is supposed to protect everyone in town, no matter what they look like. Sometimes because of things they learned, and the way the news talks about people, they might think a Black person is scarier or is going to hurt them. There are lots of people working to make things more fair. What ideas do you have?” This provides a way for your child to understand that racist behaviors are learned, allows them to continue to ask questions, and begins to show them that they can be part of the solutions to making the world more equitable and anti-racist.

As we have discussed in our previous blogs, creating a strong foundation and an environment where your child feels comfortable asking questions is so important. During these elementary school years, as they begin to learn more in school, and begin to observe what is happening around the world around them more openly, this foundation is even more important. It is never too late to begin these conversations, and it’s always a good time to build up the skills and knowledge of your children as they continue to interact with the world outside of your home more often.

Resources for your family

Family and Children’s Services: Talking to Kids About Racism, Violence, and Protests (their other resources tab is also very good)

“What is Systemic Racism” Video (kid-appropriate)

References:

Raabe, T., and A. Beelmann. 2011. “Development of Ethnic, Racial, and National Prejudice in Childhood and Adolescence: A Multinational Meta-analysis of Age Difference.” Child Development 82 (6): 1715–1737.

DeNicolo, C. P., & Fránquiz, M. E. (2006). “Do I have to say it?” Critical encounters with multicultural children’s literature. Language Arts, 84, 157-170.